Chinese Democracy

Papercuts has obtained a highly unusual document, one that concerns roughly 70 percent of all books released in Russia. It introduces a new order for selecting titles, censoring them, and discarding those that do not meet strict guidelines. What are these rules — and what do they have in common with Chinese AI as the ultimate, tireless censor?

It comes from the largest publishing house in the Russian market — so if you’re a foreign author hoping to be published in Russian, a licensing manager, scout, or agent, chances are you will be dealing with this company at one point or another. The document makes clear that the new procedure is mandatory from 5th of August 2025 for every imprint and editorial office within the group, and that every publishing director will be held personally responsible for ensuring that staff comply. Editors’ contracts will also now include a clause requiring them to:

Monitor compliance with the legislation of the Russian Federation in the production of book titles, including but not limited to: the absence of promotion of non-traditional sexual relationships, transgenderism and gender change, narcotic and psychotropic substances, the child-free lifestyle, cruelty and violence, pedophilia, incitement to suicide, pornographic materials, extremism, and extremist content. This must be enforced through the technical control tools and reporting procedures provided by the publishing house to inform management of potential risks.

The workflow systems now in place include:

a mechanism for automatically blocking publication and distribution in accordance with the Regulation whenever the above risks are identified;

a mechanism for recording in the system all decisions made at the review stage, including an electronic archive of documents confirming those decisions.

For foreign rights, the procedure is as follows:

The rights holder provides the text.

The editor submits the text for AI review.

If no risks are identified, a decision to purchase rights is made, and the AI report is attached to the application in the internal system used by all editorial departments.

If risks are identified, they are handled as follows:

a. If the content is impermissible under the law — or permissible only in passing but can be corrected with the rights holder’s consent — a decision is made to purchase the rights. The AI report is attached to the application with a note specifying the necessary corrections.

b. If the content is permissible by law only as a mention but cannot be corrected (the rights holder refuses to agree to changes), a decision is still made to purchase the rights; the AI report is attached with a note about mandatory legal labeling.

c. If the AI report leaves doubt as to whether the book contains risk, the editor may supplement it with an expert assessment and justification. The additional assessment is verified by the head of the editorial department and appended to the AI report. A decision is then made to purchase the rights.

d. If, even after verification, the content is impermissible by law and cannot be corrected (because it forms the basis of the plot, a key storyline, character development, or, in nonfiction, the main subject matter — or because the rights holder refuses to agree to changes), the rights purchase is declined.

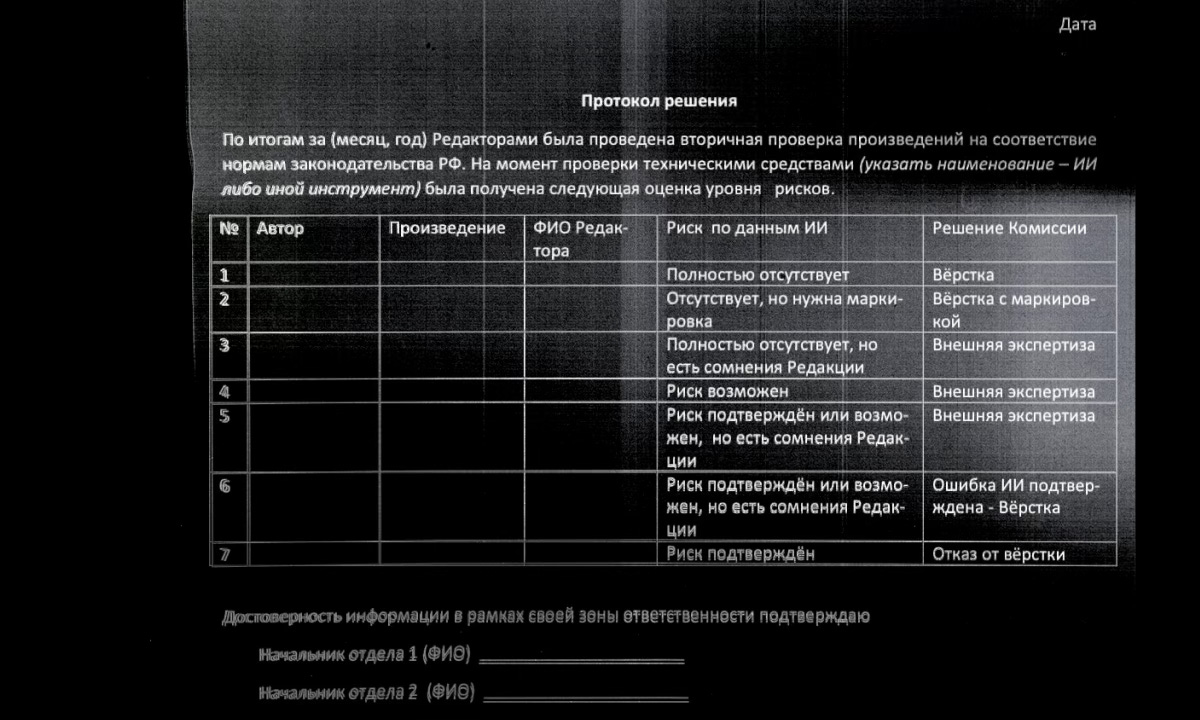

e. If no clear decision can be made, the Editorial Director convenes a Commission of department heads. The Commission makes a collective decision, documented in the Minutes of the meeting and signed by all participants, with mandatory reference to the justifications considered (AI report, expert opinions).

In doubtful cases, editors shall consult external experts, with the Russian Book Union considered the priority authority.

And what is this AI that can scan entire manuscripts in the blink of an eye and produce its own content assessment? The document doesn’t specify which AI is to be used, but according to three independent sources, the company has adopted Qwen, developed by Alibaba, the Chinese tech and e-commerce giant. Qwen natively supports Russian as well as most European languages, making it suitable for evaluating Russian and foreign titles. It should be remarked, that due to the nature of its training and design, the model reproduces certain Chinese censorship rules: it may refuse to answer questions about president Xi Jinping's policies or global affairs, or provide biased responses. Some editors also use alternatives such as ChatGPT or Telegram-based bots trained, for example, to flag mentions of “foreign agents” in texts — but this remains more a matter of convenience than policy.

Here is an example of an AI review summary:

Final recommendation: pass to additional review.

Brief verdict: The book contains numerous depictions of same-sex and other non-traditional relationships, as well as elements of a child-free lifestyle [the propaganda of which was recently banned in Russia], presented without critical assessment or condemnation, creating a risk of promotion. At the same time, the book shows no signs of promoting drugs or pedophilia, and drug use is depicted with negative consequences. An additional expert review is recommended.

The process repeats at three stages: an initial assessment, a second review before typesetting, and a final review before sending files to print — apparently to catch any “illegal content” that might appear in later stages, such as scientific editor’s footnotes. This procedure applies not only to new Russian books but also to older titles in the catalogue. The document puts it plainly:

In the event that information is discovered about books violating the law: “Discovery of information” refers both to situations involving urgent changes in legislation affecting the industry, as well as reports from citizens (including employees), partners, media, or regulatory authorities received via public contact channels (emails, letters, etc.) indicating that a book may contain prohibited content.

Sales of the book are suspended through the “Sales Ban” procedure.

A comprehensive review is carried out. The results must be submitted to the CEO for final approval.

If no risk is identified, the book returns to sale.

If risk is confirmed, the book is to be destroyed in all storage locations.

It looks like a maximum-security solution, complete with a willing army of informants from civil society (also known as “donoscthiki” — snitches in Russian) and an AI censor that never needs sleep, food, or payments for eхtra hours. But it’s not, at least yet. For now, AI still struggles with context in long texts, especially in fiction. For example, under the new procedure, Qwen once flagged a manuscript for mentioning “hashish” but failed to catch “weed” or “Crocodil” (desomorphine, highly dangerous and addictive drug notoriously known in Russia), because those words in isolation did not raise alarms.

Of course, this is a matter of ongoing fine-tuning. Perhaps in the near future Qwen will become the ultimate fireman from Bradbury’s novel, bringing the flames to books no longer welcome in Russia. This moment was announced on September 4 at the Moscow Book Fair, when Vladimir Grigoriev, head of the state department for support of the book publishing at the Ministry of Digital Development, said that by the end of October his agency, together with Roskomnadzor — Russia’s internet and media censorship authority — would present “an AI program to detect threats in texts” and make it available to publishers.

Given that two months is nowhere near enough to build a standalone machine learning system powerful enough to process a book, it looks like this will be once again Qwen.

According to Grigoryev, roughly 4–5% of all books published since August 1, 1990 can be outlawed. He also mentioned that the situation had already prompted a confidential meeting on Wednesday between representatives of the Ministry of Digital Development, the Russian Book Union, and the head of the publishing house AST (owned by Eksmo), together with the Interior Ministry.

At the end of his speech, Grigoriev said something truly remarkable:

“Ahead of us lies a long, long path of preparing for enforcement. I hope that it will be, if not humane, then at least reasonable.”

Sad but true: nobody ever expected “humane” in the first place.

This and previous letters in Papercuts were kindly supported by the Marion Dönhoff Stiftung, for which we are grateful.

Bonus: Next week, on September 13 at 17:00, we will take part in the Prague Book Tower Fair, where our authors will publicly pitch their books to an international audience. The event will be held in Russian and Czech with simultaneous translation. If you are in Prague, we warmly invite you to join us.